MMORPG Data Storage (Part 1)

Now it’s time to dive into the wonderful world of data storage for MMORPGs. If your business is MMORPG, player progress data is going to be your crown jewels and handling them with care is essential. Players tend to invest a lot of time and effort into these kinds of games, so if they lose anything they’ve acquired or accomplished in the game, they’re going to be very unhappy. Just one guy posting on reddit or twitter that his Flaming Sword of Epic Dragonslaying disappeared from his inventory, could have disastrous consequences for your game.

In this blog post I’ll try to gently introduce you to this topic, first outlining the general high-level architecture of a hypothetical MMORPG. We’ll start with something nice and simple and build on that as we discuss potential problems that we need to consider. Spoiler alert: there are potential problems aplenty.

Let’s start by getting some definitions out of the way, so we’re all on the same page:

- MMORPG: Massively Multiplayer Online Roleplaying Game, an online game characterized by a persistent shared world with a lot of players. Players’ progress carries automatically over between play sessions. The discussion in this blog applies to all kinds of online games with persistent player progress, but I’ll use MMORPG as a default moniker as most readers will relate to it.

- Client: Whatever game software running on the player’s computer.

- Game server: This is a process running either in the cloud somewhere or on some dedicated server hardware you control. A bunch of clients will connect to a game server, which will simulate the game world, and allow the players to interact with each other.

- Player progress data: In an MMORPG this will typically encompass things like inventory, quests, skills, attributes, etc. We can also call this the save game of a player. Usually games allow players to create multiple characters or profiles, but for now, for the sake of simplicity, let’s just pretend there is a one-to-one mapping between a player and his progress data.

- Database: In this context this is referring to where we store player progress data. You’ll usually need other databases, for instance somewhere to store accounts and login information, but we’ll ignore those here. We’ll assume that the client has already been authenticated before talking to game servers. For now we’ll look at the database as an abstract black box that we can store player progress data. Later we’ll look at it from a more practical point of view.

Not-so-massive MMORPGs⌗

A very simple online game might look like this:

All clients connect to a single game server process, which has its own database that it’s not sharing with any other game servers. The most basic, logical, flow as a sequence diagram looks like this:

In words:

- Client connects to game server.

- Game server loads player progress data from database.

- Player plays the game.

- Client disconnects from the game server.

- Game server saves player progress data to database.

Isn’t that just wonderfully simple? In the perfect world, this would be all there’d be to it. Unfortunately the world isn’t perfect.

First problem that will occur is this:

Server processes will crash and game servers tend to be of the more crashy variety. Game servers are complex beasts and they’ll have a lot of convoluted gameplay code that’s going to be quite hard to wrap your head around. Furthermore, on a large project, a lot of different people will be making changes to game server code all the time. Every time someone dreams up a new gameplay feature, wants to adjust something, or whatever, there will be a change to game server code. Some of these changes might come in quite urgent as a hotfix, because a problem was encountered by players. It’s volatile.

Looking at the above sequence diagram, it’s obvious what’s going to happen when the game server crash: all current players will lose all progress they’ve had for their current session. In case you’re in doubt, this is very bad for business.

Here is what we can do:

We pretty much have to store player progress data continuously during the session. Every time the player does something important, fundamentally we’ll need to save it on a disk somewhere. In that way it doesn’t matter if the game server keeps crashing, the player won’t lose anything. This is obviously going to put some strain on whatever database system you’re using and it has some practical implications we’ll discuss later.

For now, let’s return to the single-game server with it’s own database topography from earlier.

Pick your realm⌗

A problem with that architecture is that it doesn’t scale. There is a limit to how many clients a game server would be able to handle at the same time (concurrently connected users or CCU). Even if you optimize everything very carefully, and invest in some very beefy server hardware, it’ll be very challenging to have more than a couple thousand players online. Obviously this depends on the specifics of your game, some will inherently eat more server CPU than others.

The easy solution to the problem is to introduce realms:

When a player installs your game and runs it for the first time, he’ll be asked what realm he wants to play on. He could be presented with a list of creatively named realms or it could be a more primitive system where he’ll need to input the IP address or host name of the game server he wants to connect to. Regardless of how the UI is implemented, the point is that each game server is completely isolated. Each game server has its own isolated database and players on one game server aren’t able to interact with players on another.

The nice thing, from the developer’s point of view, is that this setup is still very simple. Technically it still works the same way as the architecture of the previous section, but now, when we get too many customers we can simply spin up a few more realms.

If you want to sacrifice some simplicity, you can take it to the next step:

With this setup, you’ll likely be able to handle more concurrent players per realm, as they’ll be spread over multiple game servers. Exactly how this is done depends on how your game is designed and how adventurous a programmer you are, but some possibilities could be:

- Your world is divided into continents or islands, each hosted by its own game server.

- Instanced dungeons and raids where players transfer to a different game server when they enter them.

- Instanced player-vs-player content on different game servers.

In the simplest form, this isn’t very complicated: you just need to implement a way for the client to switch to another game server while presenting the player with a loading screen.

All of this implies that a bunch of game servers will be sharing the same database, which introduces some problems we’ll need to worry about. We’ll look into that later.

Anyway, realms are also convenient in some aspects, from a gameplay perspective: it can easily get very messy with many thousands of players running around in the same game world, unless it’s very large. Realms also tend to foster a sense of community among the players playing on the same realm.

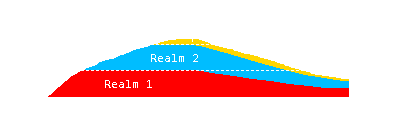

It’s not all hummingbirds and butterflies, take a look at the graph of total active players for a hypothetical MMORPG:

- Players flock to the new exciting MMORPG in town.

- When a thousand players have created characters on Realm A, you decide it’s time to open up Realm B.

- After a while Realm B is full as well and you fire up Realm C.

- But wait, the curve is breaking! Your MMORPG is not as exciting as it used to be and people stop playing.

- The number of active players on all your realms start to drop.

The graph will look very similar for all MMORPGs ever released. There will be a peak, followed by a slow and steady decline. Sure, you’ll have a bunch of smaller peaks scattered around the place, like after the release of new content, but the overall trend will be the same. For something like World of Warcraft, it took multiple years to reach the peak, but for 99% of all other MMORPGs we’re talking months, if not weeks. Looking at the graph it’s clear that, after a while, all players would comfortably fit on one realm, but you’re stuck with three of them now. You could potentially start merging realms together, but it’s pretty hard to do that without stepping on someones toes.

How does this affect your remaining players? They’ll experience how the game is becoming more and more empty. The community might organically designate a specific realm that it will suggest new players to pick, as that’s the only one still alive. Players on less populated realms might decide to jump ship and create a new character on the most populous one. This, obviously, further exacerbate the problem. If you later release new content, people will come back and everyone will want to play on the most popular realm, which will be full. Players get upset.

Let there be no realms⌗

If you don’t like the idea of dividing your playerbase into realms, you can try to cook up a game without them:

How this is implemented in practice is out in the open, but you’ll basically need a way to dynamically scale up and down by adding and removing game servers. If you have a very large open world, this quickly becomes extremely complicated. How do you divide it between game servers? If you just divide sections of it between game servers, how do you prevent all your players from just going to the same spot? What if a player shoots a fireball at another player across a game server boundary? It gets wonky. More commonly games will implement some kind of phasing where not all players can see each other, even though they’re at the same spot. This can either be implemented the easy way by dividing the world into a bunch of smaller areas with loading screens between them or the hard way, where everything happens dynamically without loading screens.

Regardless of how phasing is implemented, it can hurt the sense of community that you might get from a realm-based design. Ultimately it’s a question of what you feel is best for your particular game.

Anyway, we’re not here to talk about game design, we’re here to talk about data storage.

Keep it simple⌗

So far we’ve talked about player progress data in a quite abstract way, but in practice, how should we store it? I’ll give you the answer straight away, which is in blobs, but I’ll try to explain why that is the case.

If someone has been working a lot with relational databases like PostgreSQL, MySQL, or whatever, one might immediately start generating a bunch of SQL schema. It might seem really intuitive to do something like this:

| Player ID | Name | Class | Hitpoints | Attack Power | Experience | Level | World Location | Whatever |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tim | Enchanter | 123 | 23 | 1294 | 10 | 34.32,13.03 | … |

| 2 | Bob | Barbarian | 234 | 40 | 242 | 8 | -12.03,23.21 | … |

| 3 | Poul | Warlock | 214 | 30 | 542 | 12 | 15.10,34.12 | … |

Then you’d need a bunch of other tables, for example for inventories:

| Player ID | Inventory Slot | Item |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Main Hand | Staff of Doom |

| 1 | Legs | Amazing Pants of Fire |

| 2 | Wrists | Brazers of Killing Stuff |

| 2 | Backpack Slot 3 | Healing Potion |

| etc | etc | etc |

You’d need similar tables for quest progress, world discovery, skill points, and whatever other game systems you come up with.

When a client connects to a game server, in order to load player progress it would need to a big transactional query to read everything from these tables that matches the player ID. This data would then be used to initialize a session for the client and when the client disconnects, the session would be committed back to the database in a big transactional update.

But wait, how would that actually work? All the player data is spread over a bunch of different tables. We’d kinda have to remove all the old data before inserting the new. If Bob the Barbarian used his healing potion, we need to make sure it’s no longer in his inventory afterwards. The core approach of “load on connect, save on disconnect” isn’t really practical if player data is spread all over a relational database. Bob uses his healing potion and the game server will immediately instruct the database to remove his “Healing Potion” row from the inventory table. You’ll quickly realize that not only would you be required to update the database constantly for this to work, sometimes these updates would be very closely coupled with gameplay logic. A lot of these updates will be transactions across multiple tables, like the healing potion being removed from one table and health being restored in another.

This is simply not practical and whatever SQL database you’re using will probably not be too happy in terms of performance. Furthermore, whenever some game design element changes, you’ll likely need to change the SQL schemas and provide scary and convoluted upgrade scripts. All gameplay programmers will need to be SQL sharks.

Blobs!⌗

So, yeah, usually it’s best to just serialize player progress data into blobs. A blob is simply a binary buffer that you can store however you see fit. Exactly how you decide to turn player progress data into blobs is up to your imagination, but you could use something like Google Protocol Buffers or BSON. Don’t be tempted to use JSON as you want your blobs to be tight and compact. Personally, as a connoisseur of reinventing wheels, I’d prefer to just cook up my own system for serialization. It’s really not too complicated, you can get it to work exactly like you want it, and you can hook it directly into whatever system you have for managing player progress.

You need to consider a few things regarding serialization:

- It needs to be fast and efficient. Serialization will happen pretty much all the time, which is one of the primary downsides to using blobs.

- Blobs need to be as small as possible. You’ll be saving them all the time and you don’t want to be too wasteful with I/O.

- Your code for loading blobs needs to be backward compatible. If a player hasn’t played the game for years and logs in with an ancient blob, it should still work.

Embrace blobs and you get several benefits:

- If your blob loading code is backward compatible, it becomes very easy to add new game features and systems, as you never need to run any upgrade scripts on your database.

- When player progress data is encapsulated neatly in a binary buffer, you can juggle them around as you see fit. A player is reporting some weird bug? Just grab his blob, send it to QC, or copy it to some test server environment and try reproducing the bug yourself. You can keep blobs as simple files on your file system for debugging purposes, you can send them by email. You can convert them to Base64, print them out, and hang them on your wall. The possibilities are endless.

- You can implement a snapshotting system where the database retains old blobs for a while. For example, every week you snapshot a blob and keeps them for a couple months. This makes it easy to implement a fully automated system to restore old player progress in case it becomes relevant, like if a player got hacked and wants his stuff back.

Using blobs for player progress data is simply so convenient that it easily offsets the slight performance hit you get from constant serialization and saving.

Wrapping up the first part⌗

In this blog post we’ve taken a very high-level look at how an MMORPG could work. To summarize:

- We’ll need a bunch of game servers, connected to a central database, in which we store player progress data.

- When a player connects to a game server, we load his progress data.

- Continuously we’ll save his progress, if possible immediately after anything important happens.

- On client disconnect we make a final save of his most recent progress data.

- Realms or no realms, it’s mostly a game design decision. No matter what, we’ll need multiple game servers sharing the same database, unless we use a very simple and non-scalable architecture.

- Serialize player progress data into blobs, don’t get any crazy ideas about complex SQL schemas with a lot of gameplay logic in them. Keep the data storage system as agnostic as possible about details of the game.

Next up we’ll look at how to safely have a client switch from one game server to another.